TenableCTF 2021 Netrunner Encryption writeup

This is my writeup for the Netrunner Encryption challenge. This challenge was part of TenableCTF 2021.

You can access the task here on CTFtime.

I’ll try to make this be readable by someone who is barely familiar with these type of challenge (but who knows something about cryptography) so it will have a lot of details.

If this is something you’re familiar with, you’ll probably be bored. Maybe, you might want to just grab the code.

I have already seen writeups for this that are short & simple for someone who is knowledgeable about this.

I’m writing this for the people that are just getting started with CTFs or with cryptography challenges like this.

We got an URL that lead to a PHP webpage. It was taking one input and was returned some encrypted text probably based on that input.

We could also view the source of the page.

<html>

<body>

<h1>Netrunner Encryption Tool</h1>

<a href="netrun.txt">Source Code</a>

<form method=post action="crypto.php">

<input type=text name="text_to_encrypt">

<input type="submit" name="do_encrypt" value="Encrypt">

</form>

<?php

function pad_data($data)

{

$flag = "flag{wouldnt_y0u_lik3_to_know}";

$pad_len = (16 - (strlen($data.$flag) % 16));

return $data . $flag . str_repeat(chr($pad_len), $pad_len);

}

if(isset($_POST["do_encrypt"]))

{

$cipher = "aes-128-ecb";

$iv = hex2bin('00000000000000000000000000000000');

$key = hex2bin('74657374696E676B6579313233343536');

echo "</br><br><h2>Encrypted Data:</h2>";

$ciphertext = openssl_encrypt(pad_data($_POST['text_to_encrypt']), $cipher, $key, 0, $iv);

echo "<br/>";

echo "<b>$ciphertext</b>";

}

?>

</body>

</html>

We can observe the following things by analyzing this code:

- The output is indeed based on the input (this is kind of expected…)

To be more precise, the output is based on the input concatenated with the flag and then with some padding. - The cipher used is AES-128 in ECB mode

- The padding is not random. In fact, it is easily predictable

- The key and flag are just there as examples. These are not their actual values.

However, that didn’t stopped me from trying them anyway

AES-128-ECB

First, something about the cipher being used here.

AES stands for Advanced Encryption Standard (with its original name Rijndael, which I cannot pronounce). This is, as the name suggests, the standard for encryption and there are no known practical attacks against it when it is correctly implemented and used.

As this challenge was solved by many people, the *correctly implemented/used” part from above is surely not true in this case.

Let’s see what were the mistakes that we can observe here:

-

First, the algorithm is used in ECB (Electronic CodeBlock) mode.

This mode turns identical cleartext blocks into identical encrypted (ciphertext) blocks.

A very good example involving an image can be seen on the Wikipedia article on block cipher modes. -

And the second mistake is the use of predictable padding. By computing/guessing the length of the cleartext, we can compute characters that are used as padding

Also, the -128 part indicates that the algorithm will work on blocks of 128bits (or 16 bytes / 16 characters). This will become important a bit later.

Analyzing the length

First, let’s take a look at the length of the returned ciphertext.

An useful thing here would be to use the code and host the server on your own machine so that you’re able to add some extra logging to help you see what’s going on in there (ex: see the padding that is being used or other tricks like that).

Just don’t forget to change the URL to the one in the challenge after you confirm that your script works …

I used requests to send .. well, requests to the server and I printed the length of the returned ciphertext in each case.

The code that I used can be seen below.

import requests

import re

import base64

pattern_response = re.compile('<h2>Encrypted Data:</h2><br/><b>(.+)</b></body>')

target_url = 'http://167.71.246.232:8080/crypto.php'

def get_ciphertext(cleartext):

post_body = {

'text_to_encrypt': cleartext,

'do_encrypt': 'Encrypt'

}

response = requests.post(target_url, data=post_body)

if response.status_code == 200:

matches = pattern_response.search(response.text)

if matches is None:

print('Error. No matches were found')

print(response.text)

else:

ciphertext_b64 = matches.groups()[0]

ciphertext = base64.b64decode(ciphertext_b64)

return ciphertext

else:

print('Error. Non-200 code returned')

print(response.status_code)

def main():

for i in range(0,32):

my_input = '0' * i

ciphertext = get_ciphertext(my_input)

print('My length: %02d. Ciphertext length: %d' % (i, len(ciphertext)))

if __name__=='__main__':

main()

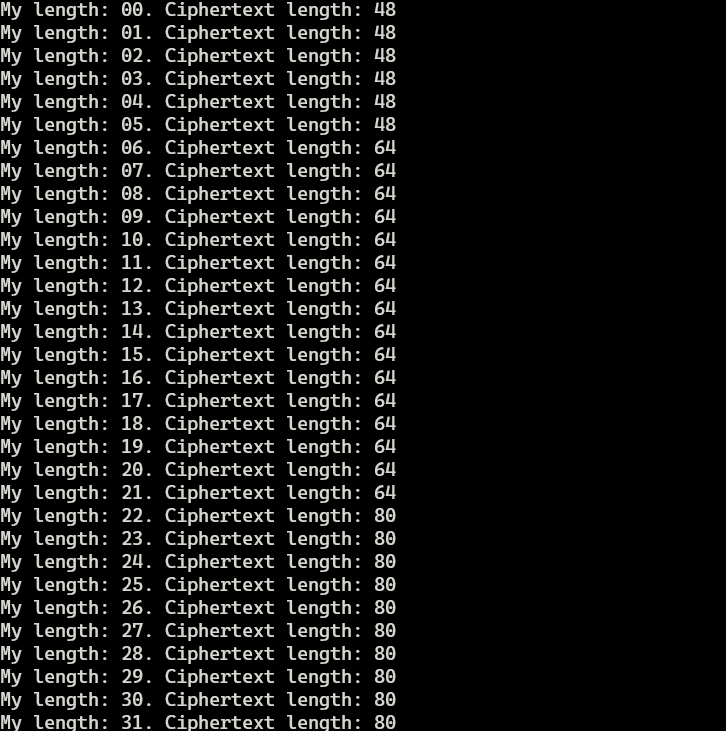

Now, let’s take a look at the result that I got

We notice the following:

- if our input is between 0 and 5 characters the output will be 48 characters long (3 blocks)

- if our input is between 6 and 21 characters the output will be 64 characters long (4 blocks)

- if our input is more than 21 characters characters the output will be 80 characters long (5 blocks)

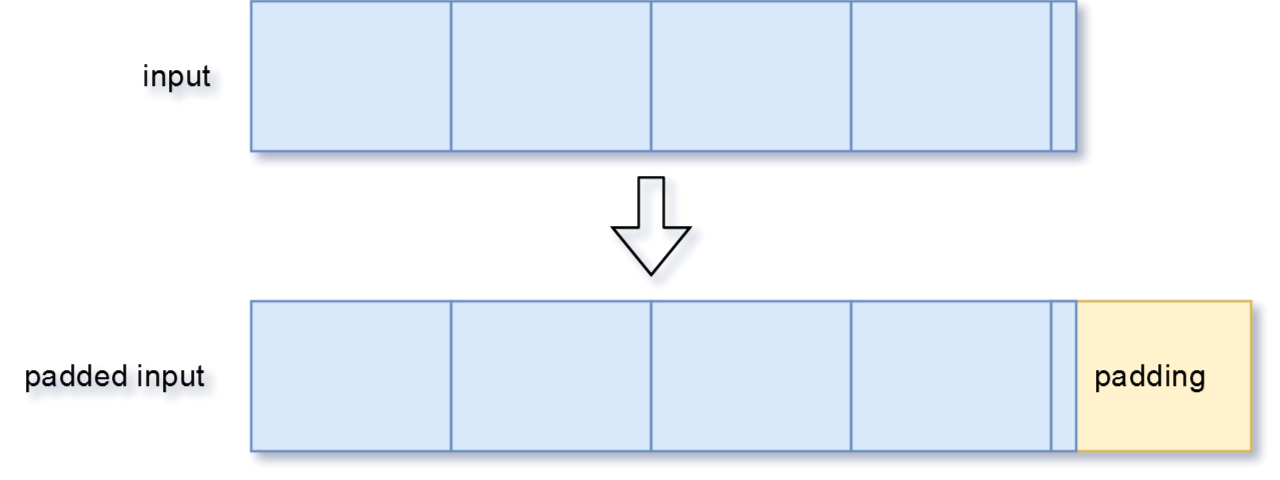

Also, because AES works on blocks of data, its input (cleartext) and output (ciphertext) will be the same size.

It working on blocks is why padding is used; if the input is not long enough, padding will be added to make sure that the input is made of a whole number of blocks.

Padding should be unpredictable / random. This not being the case here is part of why we will be able to get the flag without having the key.

Padding

Now let’s take a look at how this implementation handles padding.

function pad_data($data)

{

$flag = "flag{wouldnt_y0u_lik3_to_know}";

$pad_len = (16 - (strlen($data.$flag) % 16));

return $data . $flag . str_repeat(chr($pad_len), $pad_len);

}

Let’s consider the message to be the text that was received from the user concatenated with the flag.

First, the length of the padding is determined by how many characters are missing in order to have a complete block, or in simpler terms, a message length that’s a multiple of 16.

So 16-(length_of_message%16) characters will be added.

This also means that when the message would not need padding because it is already the ‘correct’ length, some padding is still going to be added. In fact, the last block will only contain padding in that case.

Now for the characters used for padding. The code from the pad_data function will use the character that has the ASCII code equal to the length of the padding for this.

This means that characters with ASCII codes from 1 to 16 will be used.

These characters are not printable and you won’t be able to write them by using your keyboard (ex: in the browser).

That doesn’t matter. We won’t be manually crafting the requests anyway.

ECB mode

Now to the other problem that I mentioned before: ECB mode.

It is usual to use CBC mode or any other mode that would make sure that the same block is NOT encrypted into the same output block.

However, ECB doesn’t do that. If we see two identical blocks in the ciphertext, these bocks were identical in the cleartext too.

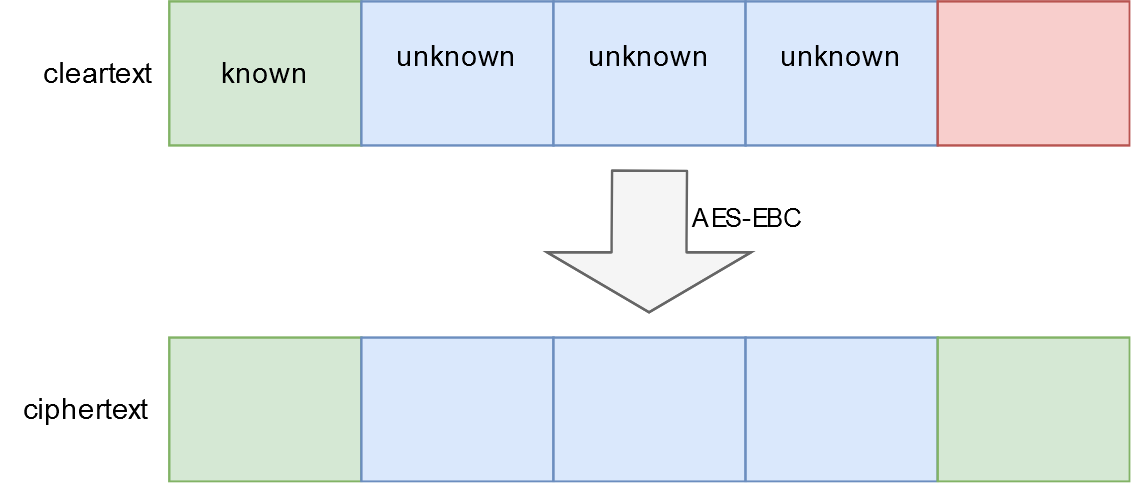

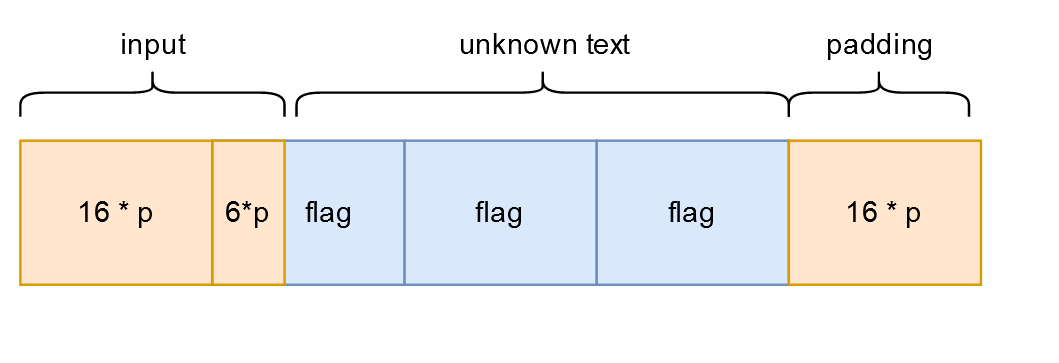

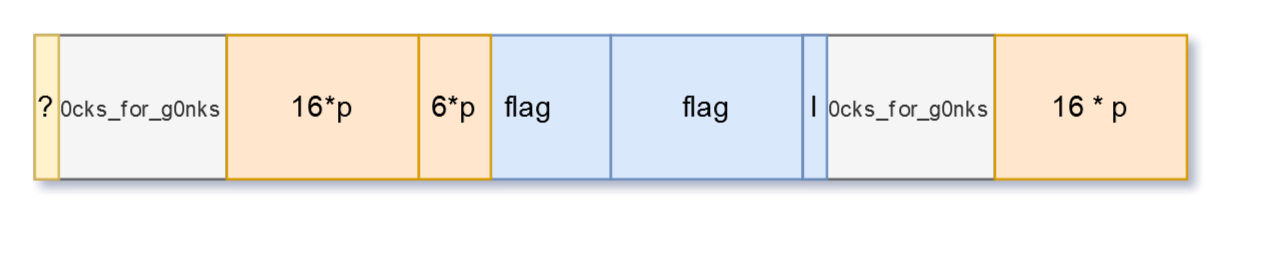

Let’s consider the example from this drawing.

Let’s ignore the blocks that are blue for this example.

Let’s ignore the blocks that are blue for this example.

Let’s consider that the following are true:

- we know this cipher used here was AES in ECB mode

- we know the first block of the cleartext (the green one)

- we can see that the first and the last blocks of the ciphertext are identical

- we don’t know the value of the last block from the ciphertext (the pink one) but we want to

Because the first and the last block from the ciphertext are identical and ECB mode was used, this means that the first and the last blocks from the cleartext are also identical.

But we know the first block from the cleartext. This means that the last block has the same value as the one that we know.

Overview on this attack

And this is exactly how this attack is going to work: we’re going to control the first block in order to make it identical to the last block.

We’ll do that by knowing that the last block contains padding characters and by trying to guess one character at a time.

We can do that by controlling how many characters from the message get into that last block.

Also note that the message has our input first and the flag last. This is what allows us to control the first block.

Now, let’s say that we go for 5 blocks (80 characters). This means that our input should be between 22 and 38 characters.

First, let’s say that we want to check if this idea works, without revealing any characters (so without any bruteforcing). This would mean crafting an input message that makes the first block and the last block be identical.

If we go for the minimum, 22 characters, we know that the last block contains only padding.

To be precise, 16 characters of padding that have their value equal to 16 (or 10 in hex).

The cleartext will look something like this:

Note: p there means a character used for padding.

Note: p there means a character used for padding.

The code for actually doing this would be:

( the get_ciphertext function was defined in the code snipped presented before)

def check_null():

padding_char = chr(16)

crafted_cleartext = padding_char * 16

ciphertext = get_ciphertext(crafted_cleartext)

first_block = ciphertext[:16]

last_block = ciphertext[-16:]

if first_block == last_block:

print('Exploit works (for null)')

else:

print('Exploit does not work')

If everything went right, we’ll see the ‘exploit works’ message and we can also print out the ciphertext and check out the blocks.

Useful trick: I would recommend printing out the base64 output and then using CyberChef to decode and view it. Chain the ‘From Base64’ and ‘To Hex’ operations in CyberChef and take a look at the blocks.

Using hex is a good idea because you will probably have a good amount of characters that are not printable.

Revealing flag characters

Now we have to move on and start revealing parts of the flag.

For our previous example, we used 22 characters for the input and as a result the last block contained only padding characters.

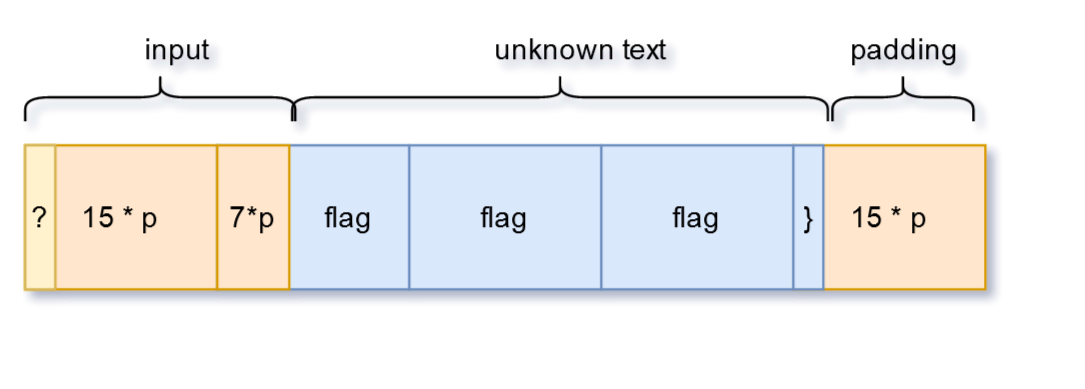

If we increase that to 23 characters we’ll now make the last character of the flag (which we can guess it’s a } because of the flag format) get in the last block.

That last block will now contain the last character of a flag (‘}’) and 15 padding characters.

We’ll have to replicate that in the first block.

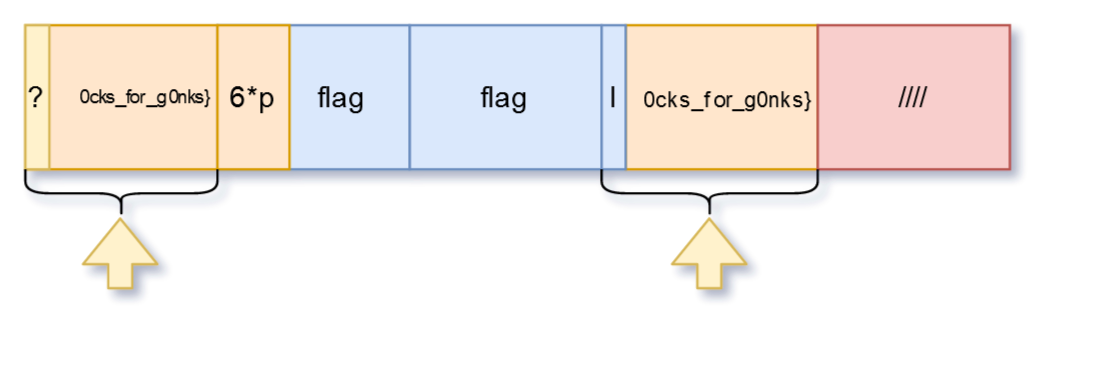

As a result, our input now will have:

- ? - the character that we are searching for. This is where we brute-force one character at a time

- 15 padding characters to make the first block have the same information as the last one

- 7 characters to get to our target input length of 23. This is needed because if we use anything else, the last block will look different.

I used the padding character for this too. But the character being used should not matter.

The cleartext should look something like this now.

Now, the code that can be used for that check.

This will use the method described above to check if the given string is equal to the trailing part of the message (the flag, in this case).

def check_block(user_text):

padding_len = 16 - len(user_text)

padding_char = chr(padding_len)

crafted_cleartext = user_text + padding_char * padding_len + padding_char * (6 + len(user_text))

ciphertext = get_ciphertext(crafted_cleartext)

first_block = ciphertext[:16]

last_block = ciphertext[-16:]

last_block2 = ciphertext[-32:-16]

return first_block == last_block2 or first_block == last_block

Note: I checked the last 2 blocks because I noticed (by using CyberChef + hex view, as described above) that sometimes it is the second last block instead of the last one.

It was that way quite consistently so I just checked both blocks. Maybe I’ll find a better explanation for this later.

In order to stay consistent with the drawings that I have, I’ll consider that I am only checking the last block.

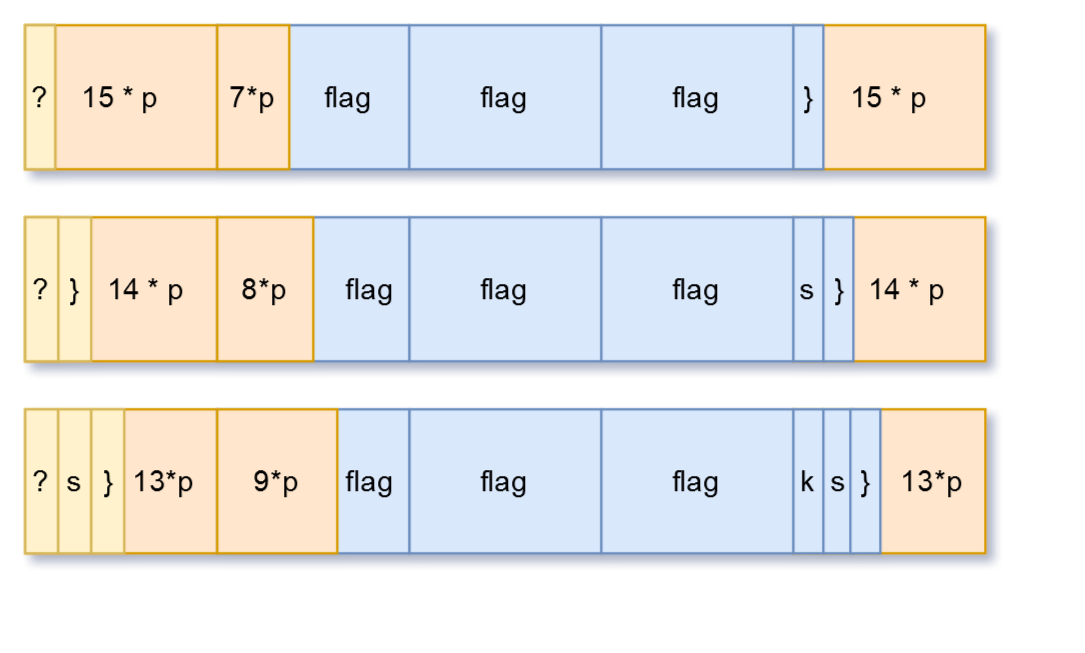

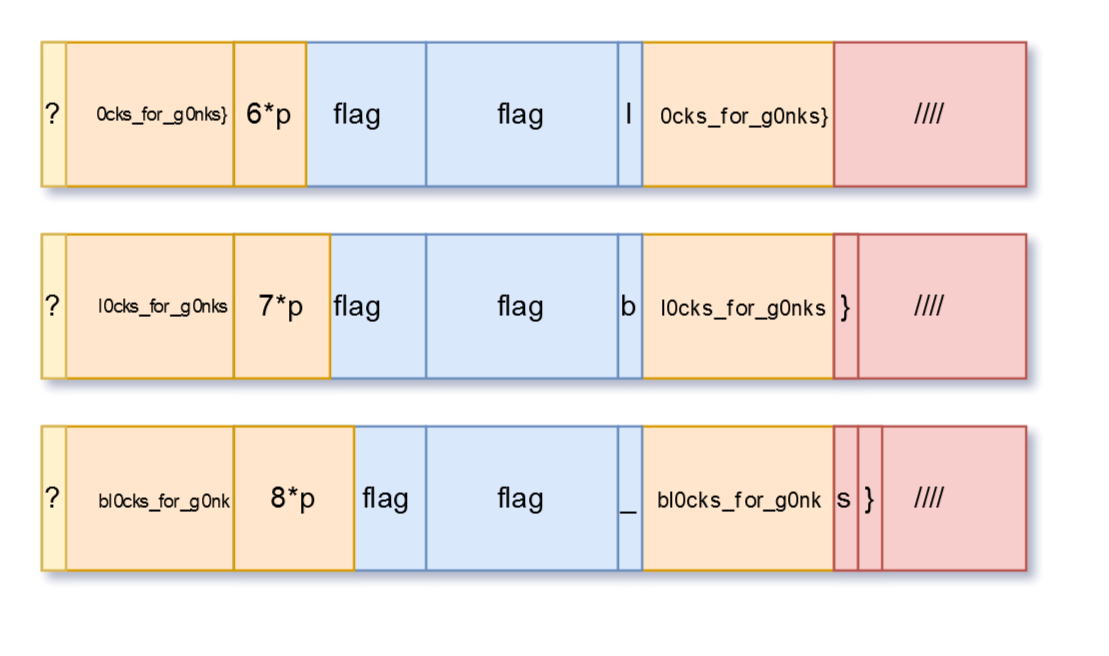

Now, after we get one character for the flag we move forward and try to get the next character.

Speaking about how the input and the cleartext blocks will look, it will be something like this:

So, in each iteration we are bruteforcing a new character from the flag.

This is the complete code used for this.

crypto.py (click to expand)

import requests

import re

import base64

import string

pattern_response = re.compile('<h2>Encrypted Data:</h2><br/><b>(.+)</b></body>')

target_url = 'http://167.71.246.232:8080/crypto.php'

def get_ciphertext(cleartext):

post_body = {

'text_to_encrypt': cleartext,

'do_encrypt': 'Encrypt'

}

response = requests.post(target_url, data=post_body)

if response.status_code == 200:

matches = pattern_response.search(response.text)

if matches is None:

print('Error. No matches were found')

print(response.text)

else:

ciphertext_b64 = matches.groups()[0]

ciphertext = base64.b64decode(ciphertext_b64)

return ciphertext

else:

print('Error. Non-200 code returned')

print(response.status_code)

def check_block(user_text):

padding_len = 16 - len(user_text)

padding_char = chr(padding_len)

crafted_cleartext = user_text + padding_char * padding_len + padding_char * (6 + len(user_text))

ciphertext = get_ciphertext(crafted_cleartext)

first_block = ciphertext[:16]

last_block = ciphertext[-16:]

last_block2 = ciphertext[-32:-16]

return first_block == last_block2 or first_block == last_block

def main():

known_fragment = '}'

known_flag = 'l'

while len(known_flag)==0 or known_flag[0] != '{':

found = False

for test_char in string.printable:

test_input = test_char + known_flag

if check_block2(test_input):

print('Char found: %s' % test_char)

print('Updated flag: %s' % test_input + known_fragment)

known_flag = test_input

found = True

break

if not found:

print('No valid char could be identified')

exit()

print('Flag discovered. Stopping')

if __name__=='__main__':

main()

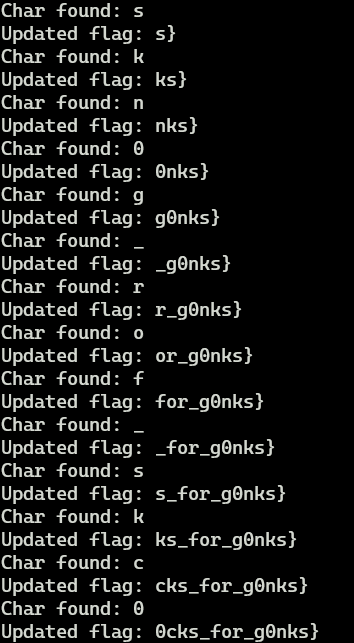

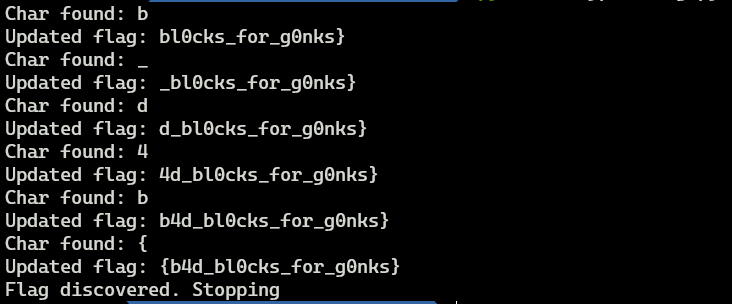

And now let’s see that code in action …

And then it stopped finding characters.

What happened?

…

We already have 15 characters of the flag and we’re looking for the 16th one. As a result, we filled the last block.

Something like this.

But remember what we noticed about the padding earlier. When you don’t need any padding because you already have a whole number of blocks, you get one block full of padding characters.

So it actually looks like this.

Not that we know a part of the message, we can approach it in a different way for the last part.

Until now, the known characters were the padding ones from the last block.

But now we know the last block (almost, we’re missing 1 char) of the message.

So, we are going to use that as the known text. And let’s start by looking for the char that we’re missing from that block.

The cleartext blocks will look like this.

The difference with what we did before is that now we are going to ignore the last block and the padding characters and compare the second last block with the known one (first block). We will compare the blocks indicated by these arrows.

I marked the last block with /// and made it red. We don’t care what’s there anymore.

I left the reverence to padding characters in the input data, but these characters that were outside the first block never mattered. You can put 0s or any other character that you like instead of the padding character there.

Also, here you can see how the next steps will look. I also displayed the characters that get into the last block. But we still don’t care about them.

And now, the code

def check_block2(user_text):

def check_block2(user_text):

known_block = '0cks_for_g0nks}'

crafted_cleartext = user_text + known_block[:-(len(user_text) - 1)] + '0' * (6 + (len(user_text) - 1))

ciphertext = get_ciphertext(crafted_cleartext)

first_block = ciphertext[:16]

last_block2 = ciphertext[-32:-16]

last_block3 = ciphertext[-48:-32]

return first_block == last_block2 or first_block == last_block3

I changed the padding character to 0s because as I said, it doesn’t matter.

And you will see the same thing that I noted before where I check multiple blocks.

Here’s the full code. I changed the main code block and made it continue from the last known result.

I think it could be made completely automated but that would consume significantly more time given the context.

crypto.py (click to expand)

import requests

import re

import base64

import string

pattern_response = re.compile('<h2>Encrypted Data:</h2><br/><b>(.+)</b></body>')

target_url = 'http://167.71.246.232:8080/crypto.php'

def get_ciphertext(cleartext):

post_body = {

'text_to_encrypt': cleartext,

'do_encrypt': 'Encrypt'

}

response = requests.post(target_url, data=post_body)

if response.status_code == 200:

matches = pattern_response.search(response.text)

if matches is None:

print('Error. No matches were found')

print(response.text)

else:

ciphertext_b64 = matches.groups()[0]

ciphertext = base64.b64decode(ciphertext_b64)

return ciphertext

else:

print('Error. Non-200 code returned')

print(response.status_code)

def check_null():

padding_char = chr(16)

crafted_cleartext = padding_char * 16

ciphertext = get_ciphertext(crafted_cleartext)

first_block = ciphertext[:16]

last_block = ciphertext[-16:]

if first_block == last_block:

print('Exploit works (for null)')

else:

print('Exploit does not work')

def check_block(user_text):

padding_len = 16 - len(user_text)

padding_char = chr(padding_len)

crafted_cleartext = user_text + padding_char * padding_len + padding_char * (6 + len(user_text))

ciphertext = get_ciphertext(crafted_cleartext)

first_block = ciphertext[:16]

last_block = ciphertext[-16:]

last_block2 = ciphertext[-32:-16]

return first_block == last_block2 or first_block == last_block

def check_block2(user_text):

known_block = '0cks_for_g0nks}'

crafted_cleartext = user_text + known_block[:-(len(user_text) - 1)] + '0' * (6 + (len(user_text) - 1))

ciphertext = get_ciphertext(crafted_cleartext)

first_block = ciphertext[:16]

last_block2 = ciphertext[-32:-16]

last_block3 = ciphertext[-48:-32]

return first_block == last_block2 or first_block == last_block3

def main():

known_fragment = '0cks_for_g0nks}'

known_flag = 'l'

while len(known_flag)==0 or known_flag[0] != '{':

found = False

for test_char in string.printable:

test_input = test_char + known_flag

if check_block2(test_input):

print('Char found: %s' % test_char)

print('Updated flag: %s' % test_input + known_fragment)

known_flag = test_input

found = True

break

if not found:

print('No valid char could be identified')

exit()

print('Flag discovered. Stopping')

if __name__=='__main__':

main()

Anyway, let’s see it in action

And this is all. Now we only have to add ‘flag’ at the beginning in order to have the required format and we’re getting our flag

flag{b4d_bl0cks_for_g0nks}